In recent days, I find poetry in places where poetry isn’t supposed to be. I suspect it’s because I’ve been steadily moving away from traditional notions of what is “poetic” and what isn’t. Some conventional poetry still stirs me, for its lyrical elegance or rhythmic sweetness, and I revisit it. But the truth is, I no longer understand why it affects me the way it does. I don’t accept it as easily as I once did.

A few days ago, I started reading a collection by an American poet named A.R. Ammons. The title is classically poetic: The Leaves Fly From the Trees Like Birds. One can immediately notice what the poet is doing: likening tree leaves to birds, and instead of falling, the leaves are flying (soaring might be a more poetic word) into the sky. Two simple metaphors: the fusion of birds and leaves, and the interplay of flight and fall.

I didn’t enjoy the collection. It felt too “poetic,” too stuffed with metaphors that seemed to exist solely for the sake of wordplay. What I felt was a kind of negative emotion that’s difficult to describe. Perhaps I can cheat a little by using metaphor myself: I felt that meaning, that distant, intangible thing, was being violated. That words were being forcibly conscripted to speak about ideas they wouldn’t naturally express. That was my second metaphor.

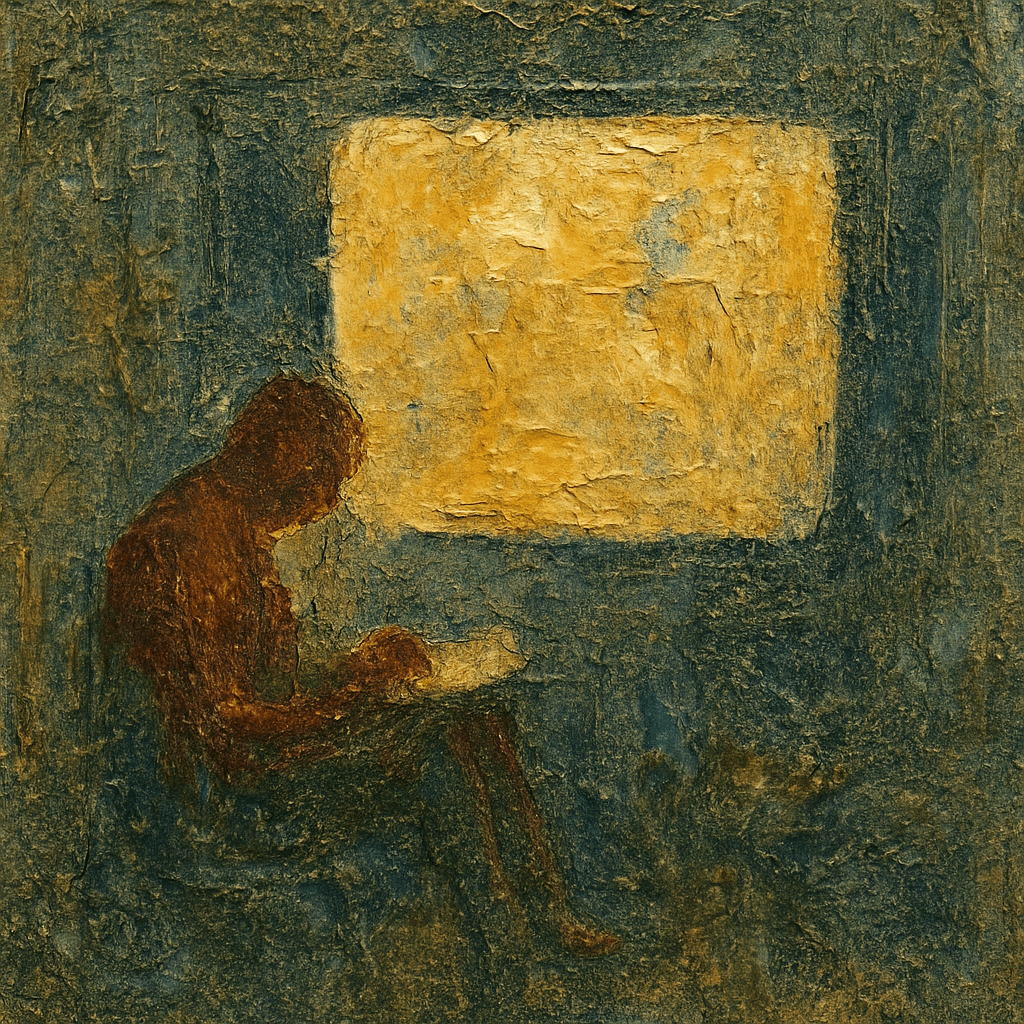

But I found poetry in Ammons’ foreword to the collection, where he describes what he calls “the most powerful poetic image I’ve ever known.” He recounts the death of his younger brother, two and a half years his junior. Not quite a year and a half after the boy passed, Ammons’ father found the child’s footprints in the mud in their yard, where he used to play. And a woman—of course a poet, overcome with grief that defied expression, tried to build a small fence and roof over the footprints before the wind could wash them away, in hopes of delaying their disappearance.

That’s not a poetic image. That is poetry itself. The act. Not the description of it, or the talking around it. Nothing else.

In one of the earliest and most well-known books on poetry, The Art of Poetry, Aristotle says that the poet doesn’t recount what happened, but rather what ought to happen. I clung to this idea for a long time, because it allows you to transcend the moment, rise above it, contemplate it, and imagine better moments. But perhaps, perhaps through repeated disappointments, I came to believe that attending to the moment is important. That meaning doesn’t construct itself. That it cannot be searched for, and therefore can never truly be found. That things which didn’t exist from the beginning, never will. Maybe I could invent a new proverb with poetic flair to express this: Staring at the river won’t make an apple grow from the water.

Poetry turns the indifferent, neutral general into something intimate and particular. The sun rises for you, maybe for your lover’s wide eyes that resemble a well for the thirsty, if you happen to be in love at the time. Not because it is a burning star around which Earth orbits while spinning on its own axis.

This doesn’t mean I want to abandon metaphor. I know its value well: how a person becomes stone without it, how metaphor has a primal place in the human soul, traveling with us from cave paintings to the emojis we send on smartphone screens. I understand the loss when reality is the only way we engage with reality.

I want to read poems and love poetry. Maybe, over time, with repeated heartbreaks, I want poems where the poet describes his lover’s eyes as a well for the thirsty, while knowing that this well is undrinkable. And says so in the same line. It is a well that lives only in language. The only way to get a real drink is to dig a real one, maybe with the same girl whose eyes resemble a dry well, for the metaphor to come full circle.

On a train heading to Upper Egypt, one of the most poetic forms of travel, where the journey lasts over fourteen hours, long enough for boredom to break down barriers between people—a modestly dressed but meticulously clean young man sat beside me. When he saw a book in my hands, he immediately, without preamble, began telling me about his mother, who was one of the most educated people in his family, despite dropping out of school in middle grade.

She passed away relatively young, after a short illness. He told me she had a phenomenal memory. Her ability to memorize and recall things was astounding, almost annoying. He laughed as he said it. She could memorize long passages after hearing them just once, just like those fantastical tales. She improvised poetry and proverbs, remembered page layouts, and recalled things he had studied years ago. It became a kind of show, not study help. She would move from room to room, doing this or that, while he followed, book in hand, tracking the lines with his eyes, comparing them to her voice. He’d trip over furniture or toys on the floor, waiting for her to make a mistake. But she never did. “Not once,” he said with certainty, “not even a comma.”

And then she died. And what shocked him was that all those texts she’d held in her mind, had vanished with her. He didn’t know where they had gone.

He told me he went a bit mad. For several months, he surrounded himself with all the textbooks she had helped him with, trying, for reasons he still can’t explain, to memorize them all. He shook his head, saying that thankfully, it passed. But back then, it felt like the only logical thing to do. Especially since she had kept all his old books. He wanted to transfer everything from her mind to his. Of course, it didn’t work.

This will remain one of the strongest “poetic images”, though it is, in truth, stronger than poetry itself. A boy sitting on the floor in his house, clutching old, worn textbooks, trying to load everything he sees into his head. Another fence around footprints the wind will erase.

Leave a comment