What Makes Us—Humans—So Different? The eternal question of humanity, one we begin with and return to. With each new attempt to explore an answer, we complete part of an ever-changing and evolving picture. While new knowledge in this area is endless, continuously adding to our understanding, it also serves as a reminder of how little we truly know and of the vast difference between our contemporary existence on Earth and the journey of humans and their relatives over thousands of years.

The 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Svante Pääbo, a geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, for his groundbreaking research in this enigmatic field. According to the award’s press release, Pääbo accomplished what was once considered nearly impossible: sequencing the genome of the Neanderthal, one of the extinct relatives of modern humans. He also discovered a new species of ancient humans, known as Denisovans.

Fossils or Genes?

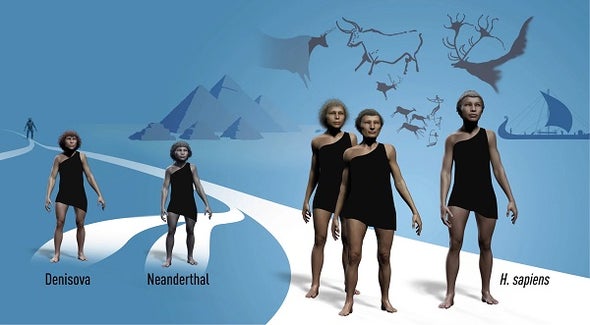

For much of scientific history, the study of human origins and evolution was the domain of paleontology and archaeology. Paleontology examines preserved remains of organisms that have survived through time, while archaeology studies the traces left behind by these beings. Research in these fields has provided evidence that our species, Homo sapiens, emerged around 300,000 years ago in Africa. Our closest relatives, the Neanderthals, appeared outside of Africa—specifically in Europe and western Asia—about 400,000 years ago before going extinct, a subject still widely debated among scientists.

Around 70,000 years ago, a pivotal migration occurred. Groups of Homo sapiens left Africa and settled in what is now the Middle East before spreading across most of the world. This means that for tens of thousands of years, Homo sapiens and Neanderthals coexisted in the same regions of Eurasia. But how did these two species interact? Can we even know? Archaeology reaches its limits here, as it relies on what is physically discovered rather than what can be inferred.

The introduction of genetics into the picture changed everything. In the 1990s, scientists first sequenced the nearly complete human genome, allowing them to study genes both individually and as a whole. This opened the door to comparing modern human genes with those of our ancient ancestors—provided that ancient DNA could be successfully extracted from fossils and archaeological samples.

From Egyptology to Ancient Genomics

Interestingly, Egyptology served as a bridge between paleontology and genetics for Pääbo. He studied Egyptology at Uppsala University in Sweden, and through his PhD research, he demonstrated that DNA could survive in ancient Egyptian mummies. At the time, this was merely a speculative idea, but it laid the foundation for future advancements.

Pääbo’s biggest challenge was the scarcity and fragility of ancient genetic material. Most of the DNA recovered from fossils is damaged, chemically altered, or contaminated with modern DNA. Identifying authentic ancient DNA became a major obstacle.

His key achievement was developing new techniques to extract, amplify, and read degraded ancient DNA, allowing scientists to reconstruct the original genome. This gave birth to a new field of science: ancient genomics.

An Obsession with Cleanliness

Pääbo’s success underscores a fundamental yet often overlooked aspect of scientific discovery: breakthroughs come from meticulous, methodical processes rather than sudden flashes of genius.

One of his first steps was designing ultra-clean laboratory environments to prevent sample contamination, ensuring thousands of specimens remained viable for precise genetic analysis. While this may sound simple, maintaining such conditions is extraordinarily difficult, given the fragile nature of ancient DNA.

The next step was developing statistical techniques to identify and exclude modern DNA contamination from ancient samples.

In 2010, Pääbo and his team published a groundbreaking paper in Science, comparing the genomes of modern humans and Neanderthals. Their findings confirmed that both species share a common ancestor who lived around 600,000 years ago. Moreover, their research proved that Homo sapiens and Neanderthals interbred, with 1%–4% of modern human DNA originating from Neanderthals.

Further research revealed that this interbreeding was not limited to Neanderthals—it also occurred with Denisovans and other archaic human groups. These genetic exchanges introduced important genetic adaptations, increasing human survival chances in new environments.

Why Pääbo’s Work Matters

One of Pääbo’s most significant contributions is his ability to track how genes flowed between different human species, offering insights into early human migrations and physiological adaptations.

For instance, some genetic variations inherited from Neanderthals help humans survive at high altitudes. A particular gene, EPAS1, is common among modern Tibetans and helps them thrive in low-oxygen environments. Similarly, some immune system genes inherited from archaic humans influence how we respond to infectious diseases, including COVID-19.

Pääbo’s discoveries also shed light on genetic risk factors for modern diseases, such as schizophrenia.

What Makes Humans Unique?

Humans possess abilities unmatched by any other species—complex language, large-scale societies, art, culture, and advanced communication. While Neanderthals lived in groups, had large brains, and crafted tools, their development remained limited to rudimentary early attempts over hundreds of thousands of years.

In contrast, modern human distinctiveness stems from numerous genetic changes that shaped our present capabilities. Studying ancient genomes allows us to identify the key genetic traits that set us apart.

According to the Nobel Prize committee, Pääbo’s work was crucial in defining the differences between modern humans and our closest extinct relatives, the Neanderthals. His pioneering research has transformed our understanding of human evolution and why we, uniquely, became the species we are today.

This Article was originally published in The Arabic Edition of Scientific American.

Leave a comment